Instagram and The Myth of Social Changemaking

Can bite-sized content machines help fix our society? Should we expect them to?

Being critical of social media sites is nothing new. Pointing out their negative aspects seems both incessant and inconsequential; a dripping faucet that nags at our psyche but never quite brings us to meaningful action. Few people in the year 2024 would question that social media causes harm and nearly everyone agrees that there are better uses of our time. Despite this, those magnetic little icons continue to beckon our thumbs, day in, and day out.

There’s much complexity in these millions of interactions. For some it’s a shame-filled scroll of secrecy, for others it’s the only way to successfully run their business, and for the younger gradient of the population, it’s simply the only life they’ve ever known.

Because everybody’s bubble of media intake is singular and distinct, it can be quite difficult to address everyone about their social media habits at once. Every glowing rectangular abyss is a ’cosm uniquely tailored to each individual, so things that make sense inside one circle of influence may have zero resonance elsewhere. But there’s one widespread phenomenon on social media that I’m finding more and more urgent to examine. It’s actually one of the primary reasons I decided to migrate to Substack in the first place. The problem? When people attempt to get deeper than the platforms were designed for. Specifically, with politics.

Each of the big platforms gush with abundant opportunities to share whatever it is that you’re personally passionate about. These companies gave us the infrastructure to delight in an all-day virtual bazaar of worldly digital ephemera snack-packed alongside our most treasured people and topics. Being innately social creatures, it’s no wonder these sites circled the world so fast. But as our lived reality has become increasingly exploited for political gains, we’ve been subjected to a social media experience evermore rife with explicit political messaging. Never before have we had access to so much information about so much going wrong.

So it seems natural, for many, to post about it. The Issues! So many Issues! The Problems, The Solutions, and all the chatter and back-and-forth that surrounds them. If you wish to spread the good word about these dire crises of our times then social media at first appears like the perfect place to do so. Today it’s become routine to wake up, open your app of choice, and get bombarded with horrifying, nerve-clenching news that somehow always consists of exactly two sides and demands that the viewer must take one (conveniently for you, the sides always happen to be Good vs. Evil, so the choice is posed as something simple and morally obvious. You’re not evil, are you?!)

How did we get here? (briefly)

We used to have a giant 24-hour public square called Facebook. People used it to discuss all matter of topics, from travel tips to relationships to dentist recommendations. At it’s height in the early 2010s, users checked the site so frequently that you could use your public profile to look for a ride to work or see which bar your friends were at—and get immediate, real-time results! Can you imagine?! Visiting the lifeless ad-dominated hellscape Facebook has become today makes this colorful past hard to remember. But inevitably, as our political environment intensified, (I’ll mark the beginning of the upward trend around ~2014) so too did peoples’ use of the platforms. And unlike the other popular offerings at the time (namely Twitter, Instagram, and Vine), Facebook enjoyed a mass public buy-in that no other platform could match.

Everyone was there. Not just the 14-25 year-olds. Millennials, Gen Xer’s, Boomers and a surprising number of grandparents all adopted the tech and all had seats at the table. This made the public square incredibly powerful, and more than a bit socially dangerous. If young cosmopolitans wanted to post a passionate political dissertation to win points with a niche group of their progressive college friends, they would have to do so in the same space that their conservative aunt wished them a happy birthday. In a sense, discussions had to happen in the light of day.

This dynamic was many things, but comfortable wasn’t always one of them. As political discourse advanced, an elaborate choreography of division started to take form. A user would brazenly post about a controversial topic, and among the cheers from their inner friend group, they could also expect a stir of disagreement from the farther reaches of their network. Co-workers, past acquaintances and distant cousins all had the opportunity to descend upon the post to express their discontent. The comment section became a battlefield with very few winners. Some people thrived from the addictive sportsmanship of these constant mini dramas, firing off daily political memes just for the sparring matches that would (hopefully) ensue. This dynamic came to define the era of social media discourse, regardless of whether or not you personally participated in it.

How Instagram Changed Things

While the shared experience of Facebook rapidly slid off the rails, Instagram was steadily gaining popularity. A lot of people my age quietly left the barrage of articles, infographics, bullies, and the half-baked arguments that accompanied them. It was becoming obvious that the value of the platform had been waning—compromised by everyone from dime store scammers to foreign bots to the increasingly suspicious motivations of the people in charge (the term “Big Tech” only first appeared in late 2013, but helped to underline the public’s growing distrust of Silicon Valley’s exploits). By the end of 2016, a huge swath of the population had already migrated to greener pastures.

Instagram offered something different. Something undemanding and easy to look at. Where Facebook was busy trying to be everything to everyone, Instagram was a haven of simplicity. A more focused experience that provided the quick dopamine we craved without the chaos and inconsistency of the place we left. It was optimized to show us things we loved and its modern aesthetic ushered in a new age of mobile interfaces. The filters and editing tools provided a renewed sense of creative liberty, and the "Stories" feature gave people something they didn’t even know they wanted: impermanence. The fact that everything posted to your Facebook wall remained a permanent fixture that people could view after the fact added a subconscious layer of consequence to your postings. To many, knowing full well that a spicy hot take could be dug up and reevaluated years down the line felt more like a liability than an advantage. Instagram saved us from this scrutiny, allowing us to post in peace.

All of these benefits were, of course, illusions. False promises repackaged and resold to perform the same function as the old model, more targeted and sophisticated than ever before. Techno-pageantry, and nothing more. But what is it that makes Instagram so particularly toxic to public discourse?

Engineering Addiction

Every feature—down to the smallest minutiae—has been calculated to keep users on the app as long as possible, and keep them coming back habitually. This fact alone made Instagram incredibly valuable from the outset (Facebook wouldn’t have spent that cool billion without some pretty eye-popping evidence to this effect). They’ve honed dozens of techniques to accomplish these ends. Some of them you may have clocked over the years, but the most effective ones are often the most subtle.

For instance, Instagram is geared to never show you something twice. Stories, Posts from friends, Suggested Reels, even some messages in your private inbox have a ‘disappear’ function. One important purpose this serves is that it makes the experience feel more expansive. There’s always something more to discover, and if you just stay a little longer, you might see something you really like. They also majorly pared down the progress bar and ‘scrub’ function, which have been standard features for all videos on the internet since the '90s. Do you think it was an accident that they make it hard to tell how long a video is? Is having to hold your finger on a video to pause it a ‘user-friendly’ design? Or have all these cunning UI features solely been implemented to increase feelings of scarcity and maximize screen time?

Introducing the notion of scarcity at every turn keeps users on the app longer by constantly reinforcing the fear of missing out. This might be the day your friend finally shares some big news, or the beginning of a new viral topic that will define the months ahead… Imagine what you might miss if you don’t log on today… Just scroll a little further… Let’s use the Suggested Reels section as an example. Introduced by the app in 2020, the feature now appears at random in your feed (though this ‘randomness’ is also precisely calculated to emphasize the addictive experience) and shows you things the algorithm thinks you’ll like. The moment you decide to watch one, a cascade of triggers will occur on the back-end.

First, the algorithm notes the initial appearance of the preview you were exposed to, for future reference. Advanced AI tools scrutinize every element of the three-second preview for clues about what your brain was drawn to. It evaluates how long you watch, and if your phone is a more recent model, the app is also most likely using your front camera to track eye movement (side note: have you ever wondered why the caption and all other info is presented right in front of the video, instead of separated by a border? This is a strategy developed by TikTok to make the video feel more immersive and tease your eye with additional stimuli while ensuring that anywhere you look will always be directly at the video).

You may have also noticed how the messy new layout of video sharing only allows for the first few words of the caption to be shown, and you always have to click to read the rest. This is another sneaky tracking technique. If you open it, the app knows for sure that you’re engaged enough to care about what it says. Same if you decide to read the comments or tap any of the other engagement options. Every element has been sectionalized so the company can obtain (and sell) precise watch metrics. If you swipe away before it’s over, the Reel is down-ranked, (but the algorithm will likely keep trying to show you similar content for a while, because it knows something about the preview pulled you in). An enormous number of datapoints have been secured before you even consciously decide to type a comment or tap 'like'.

FOMO psychology kicks in by teaching users that if they leave a video without interacting with it, they may never be able to find it again. In the olden times of browsing the web, one could bookmark a page, leave a tab open, or create a list of sites they wanted to save for later. These practices were conducted in the privacy of one’s own home, without the prying eyes of dozens of third-party organizations vying for access to your activity. This model was obviously far too primitive for Web2.0, which refuses to serve users unless it can simultaneously extract sellable data from them. The app didn’t have to design an experience with so many annoying breadcrumbs and miniature stakes—but passively training users to follow, like, comment, save and share everything they find valuable is an exceptional way to build comprehensive psychographic profiles that can predict their deepest emotions. Not to mention another powerful way to ensure a habit-forming product.

The supply side is equally affected. By manufacturing a constant demand, the content creators who make the videos have been conditioned to post as much as possible to stay relevant. The effect has been similar to CNN and the advent of the 24-hour news cycle. By framing creators’ accounts as content machines to feed hungry followers every hour of the day, Instagram abandoned quality standards and hatched a new industrial complex. Unlocking the keys to virality has grown to be more important than whatever it is you may be posting about, illustrated here by Yasin Mammeri:

Brain Chemistry

If Facebook stumbled upon the formula to keep users enraged (prioritizing content likely to stoke fear or aggression) Instagram has mastered the science of keeping users jauntily sedated. Facebook’s strategy for the last ten years has been rooted in triggering the release of endorphin chemicals like epinephrine and norepinephrine, while Instagram primarily traffics in dopamine. Both approaches are addicting in different ways, but can derail the discussion of complex topics equally.

Dopamine is a fickle chemical. It can be produced in enormous amounts when something feels new and exciting, but results quickly diminish once the novelty wears off. Instagram knows this and exacerbates it through variable reward schedules, excessive and redundant notifications, quantification of social validation, and even the very color choices of different features. Constantly blasting dope down that mesolimbic highway in your brain hardens your pleasure receptors over time, making the experience less enjoyable. But despite the diminishing returns, the motivation to repeat the behavior will continue if you don’t have a good substitute; explaining our culture’s compulsive, love/hate preoccupation with phones.

Hijacking Your Brain’s Limbic System & Talking Politics

My guess is that a number of readers already have a baseline understanding of what I’ve laid out so far. Most people probably don’t need to see a study to be convinced that social media can harm attention spans, relationships, mental health, and cause FOMO (though there are many to choose from, including internal reports from Meta itself). But as we enter another excruciating year of global election politics, it’ll be helpful if we had some shared agreements about what social media is doing to us and who benefits when we use it for it “activism”.

Using these apps is changing the nature of our discourse and our decision making faculties.

This essay is getting long, so if you need to take a break, I invite you to pause. Go outside, get a snack or refill your tea if it pleases. Because I really want us to be on the same page about the following: Each of the shortform social media apps (Instagram, TikTok, Threads, Twitter/X) are bad for politics. Full stop. And though a lot of people might already agree with this, their reasons are often limited by predictable partisan outlooks. American liberals assume the apps are bad because they give people they don’t like a platform to spread hate and misinformation, while conservatives assume they’re bad because they’re part of the woke media. Both of these viewpoints contain authentic truths, but they fail to get to the heart of a much more insidious design problem. Namely, that using these apps is changing the nature of our discourse and our decision making faculties.

With the hullabaloo over recent TikTok legislation, you’ve probably already seen folks come forward celebrating the ways TikTok allows them to educate, connect, and generally help the world. Bleary-eyed stories outlining the economic freedom and sense of place the platform provides accompany theories of how Congress only wants to pass the law because they’re afraid of the power TikTok has to influence upcoming elections. That’s all fine and good. Let the people make their case. But please don’t let their passion misguide you into thinking TikTok, Instagram Reels, and other bite-sized content is somehow helping preserve democracy. These are the master’s tools that Audre Lorde spoke about, and need to be understood as such.

These sharing platforms are not leading us into some kind of glistening technotopia; they’re deteriorating our very capacities to assess what’s going on.

Leveling public discourse had many positive impacts throughout the internet age. Tech companies helped democratize the media, and gave regular citizens a voice. This helped neighborhood interest groups grow into global movements, and it helped individuals come of age. These companies certainly provide some value, or else we wouldn’t keep coming back every day. But we need to be honest with ourselves. What started as a promising reorganization of power has swung back around to scaffold the most imbalanced and unequal society of the last 500 years. To me, the truth has never been clearer that these sharing platforms are not leading us into some kind of glistening technotopia; they’re deteriorating our very capacities to assess what’s going on.

Minor differences in formatting can have enormous impacts on dialogue, and our new platforms have us racing to the bottom of that totem without even realizing it. Imagine how discussion changes when it transitions from in-person to a Facebook or Reddit forum. We’re well aware of how people grow aggressive and obnoxious behind the wall of anonymity, but what about the ways a format itself begets different engagement? Those with stronger writing skills and more time on their hands will inevitably have an upper hand when arguing against someone in a written thread. Those surrounded by their own peers (a comment section hosted on their own post vs. a stranger’s, let’s say) will enjoy backup support from friends who can dogpile an agitator.

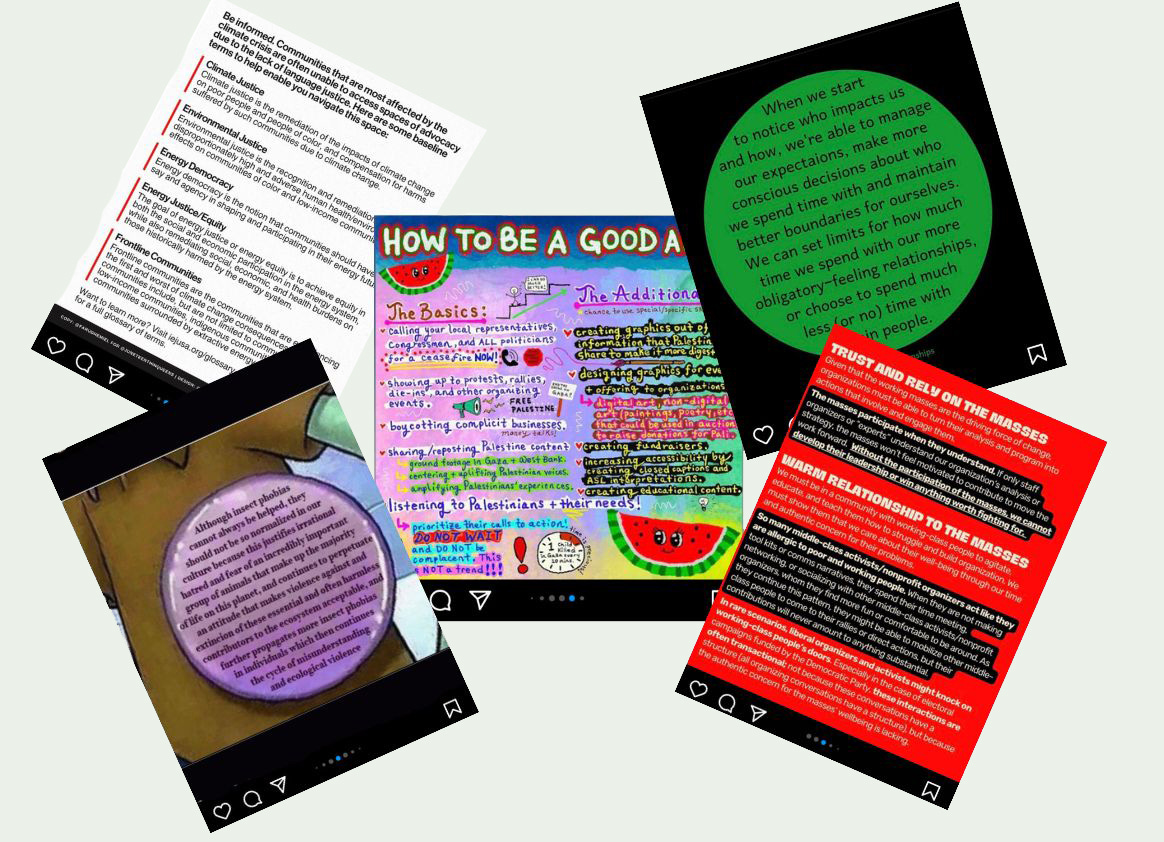

But for all their flaws, at least Facebook’s old comment sections allowed a readable, inviting space to edit, proofread, and parse your thoughts. If you had a lot to say, you could separate paragraphs and add photos, links and other media to substantiate claims and make your small essay look more approachable. If there was a lot of activity on a post in your network, Facebook would periodically return it to your feed to show you how the drama was unfolding. Instagram has explicitly done away with this functionality. People no longer appear with their real names, but handles. The most prominent features on their page are artificial clout stats like how many followers they have. This subconciously affects the way you’ll interact and has a tendency to poison the well of conversation. The app also limits character counts, and because of their sleek mobile layout, even a 300-word comment will look like an impenetrable wall of text. In essence, they made reading and writing a chore. But how will we fare when all our most pressing social ills are too complex to fit into a ten-slide carousel, or a three—or even a ten-minute video?

There are political/economic/philosophical underpinnings behind our collective destruction, and those are what we need to change. It can be tempting to conclude that a digestible buffet of Tweets, Reels & Toks are good tools to effect that change, given their impressive ability to spread ideas quickly. But we need to remember that every player in Big Tech is diametrically opposed to the very political and economic changes you might like to enact. As such, there is a built-in glass ceiling to change that can be made through social media, and the platforms owners’ are absolutely committed to making sure you never break through it.

From The Arab Spring to BLM: Did Social Media Spur An Age of Enlightenment?

The myth that social media was creating a Braver, Free-er, More Connected New World held water for a time. An early and famous account that seemed to prove the point of social media’s capacity for social good came in the form of The Arab Spring. Techno-optimists embraced the idea that Facebook and Twitter helped free Middle Eastern and North African countries from oppressive government regimes, calcifying the era into a poster child for online activism. Big Tech was winning in every other arena, why shouldn’t it start innovating democracy itself…?

These exciting claims have dimmed in hindsight, as we learned that much of the story of saviorism was overblown or even counterintuitive to the goals of the revolutionaries. The reality is that American tech firms in fact supported and collaborated with repressive governments, failed to effectively moderate extremism, and often even suppressed political dissidents by suspending and disabling their accounts. Cherry picking successes of The Arab Spring movement to prop up some semblance of street cred just rubs salt in the wounds for millions still living inside states that are—in cases like Syria, Yemen and Palestine—far worse off than they were before the uprisings went online.

But for most of the 2010s, Big Tech enjoyed the reputation as a crucial outlet for the underdog. The idea that social media was to be used to advance activist causes had been fully and unquestionably integrated into the operating system of public life. By the end of the decade, finding a person who hadn’t used their social media accounts as a form of protest would’ve been like finding a person who’d never eaten fast food. Possible, but implausibly rare. The invention of online activism reached a fever pitch in the dog days of 2020, with Black Lives Matter, Covid-19, mounting economic crises, and another nightmarish election showdown roiling through Americans’ virtual spaces. No stone went unturned.

Much time could be spent debating the merits of these campaigns, but in short, the impact of lashing through that torrent of posts, Stories, Tweets, dances, filters, slogans, and profile picture alterations seems to have been overtly negative—irreparably damaging the function of discourse. And while each individual surely felt like they were adding helpful contributions to valid causes at the time, the effect of turning social movements into memes has a complicated track record, and often doesn’t produce lasting results. In addition to this, many of the messages people thought were coming from grassroots activists were in fact, fake. These strikes alone could condemn the apps as political tools, without even opening the deep rabbit hole of shadow-banning and censorship they do in collaboration with various state departments. Every time you post about something (especially something political) it adds to a stylometric analysis that the app and anyone else looking at your data will use in order to impersonate, manipulate, or provoke you in the future.

Who Remembers Cambridge Analytica?

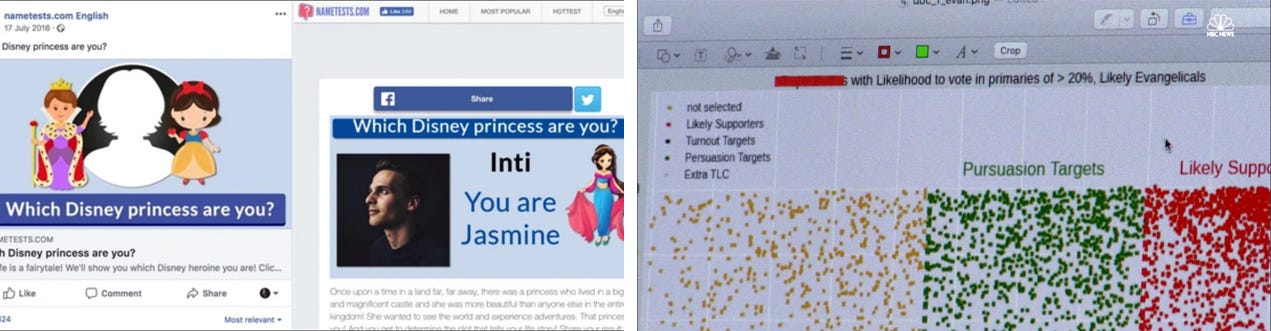

This brings up yet another concern. It’s probably been a couple years since you last heard the name Cambridge Analytica. To refresh, they were a forward-thinking PR firm who’s main business operative was to use innovative psychological tactics to influence political campaigns. They worked as a hired gun for a wide range of candidates, but seemed to find a certain joie de vivre aiding right wing despots.

They tampered with over 200 elections around the globe. But when it was discovered that they covertly collected data from hundreds of millions of Americans through things like personality quizzes and then deployed a flood of messaging to coerce voters to sway Brexit, Trump and other elections… It became one of the biggest scandals since Edward Snowden pulled the rug from under the NSA. Here’s a quick clip from documentary film The Great Hack (2019) that helps illustrate some of their insidious methods:

From this clip, we get a visceral image of what a passionate social movement can look like. It may even remind you of similar movements on your home soil, which makes it all the more jarring to realize how much of it was engineered by a subversive overseas company. How many online quizzes have you filled out in the last ten years? How many fun surveys or viral participatory trends swept you into an updraft, only to be forgotten days or hours later? How many times has your own data already been used against you? How much of it might be stowed on a private hard drive, waiting to be analyzed and used during the next political eruptions?

All this brings me to still more questions. Was Cambridge the only bad actor playing psyop wargames in the 2010s? Were they even the worst? Facebook faced a cannonade of criticism for colluding with Cambridge and potentially influencing the outcome of a major US election, but this didn’t result in virtually any new regulations. CA went bankrupt and shuttered before court proceedings even finalized, but their parent company SCL Group and it’s Behavioural Dynamics Institute are still open for business. And as is so often the case with industrial corruption, none of the executives in charge have faced serious penalties—and have instead simply opened up shop under new names. Which begs the question; who will oversee the next Great Hack? What kind of psychological manipulation is in store for the 2020s?

If you’ve learned anything over the last couple of years, it’s plain to see that TikTok is immensely powerful. Its algorithm is the most probing, its interface the most addicting, and its mainstream adoption the most rapid. And whether it gets banned from the US or not, its design is going to define our coming political epoch. Along with advancements in generative AI, it’s safe to assume that whatever happens from this point forward is going to massively eclipse any of the information warfare we’ve seen previously. And despite all the attention paid to Facebook as the biggest and most ill-willed of them all, the new platforms taking its place are positioning themselves to be leagues more disastrous than Facebook could ever be.

I can imagine what you’re thinking right now. You’ve seen enough documentary films to know that we’ve made it to Act Three. Isn’t this supposed to be the 'Solutions' section? “What are we supposed to do, Cal, since you’re so goddamn smart? Not discuss politics online??” And this is where you might be disappointed. There is likely a future when the world looks back at our time with disbelief and knowing remorse. Like seeing old photos of pregnant mothers drinking alcohol or cyclists smoking during the Tour De France, it will be hard to fathom how our culture was so hellbent on destroying itself. This perspective is already gaining disciples, but for now, we’re at a structural impasse. We know that constantly updating our Story with tirades about genocide or racial violence or abortion or school shootings is doing little besides harming the mental health of you and your peers—but we do it anyway because staying silent doesn’t feel appropriate, given the scale and severity of the problems.

Changing the views of someone in your immediate network is a noble pursuit. But doing it effectively has far more to do with trust and compassion than anything else. If you’re going to take any advice from me, let it be to focus on strengthening your immediate relationships and building community ties that are more than transactional. Repeatedly subjecting someone to biased news articles and TikTok re-shares from people they don’t respect isn’t going to get you there, but accepting their innate humanity might. Changing the views of your elected officials is even harder. All the 𓂆 ᖴᖇᗴᗴ ᑭᗩᒪᗴ𝓢тIᑎз 𓂆 posts in the world will not change the fact that Mitch McConnell, Hillary Clinton, and Chuck Schumer have each received millions of dollars from Israel’s lobbying efforts. Joe Biden has taken nearly $5 million alone. Recognizing our respective spheres of influence is the first step to meaningful action, and frankly, geopolitics is not an area where average citizens have tremendous reach.

I hope this doesn’t sound defeatist. The purpose of this work is not to sow despair. My hope is that having a better understanding about what social media is good for—and what it isn’t—can help us all move more tactically in the future. I’m not so naïve to suggest that we should all stop using these platforms (though the idea is compelling), or that people who use them towards political ends are stupid for doing so. But perhaps in reading this, you might be inspired to think more creatively on how to navigate our increasingly bewildering state of affairs. There’s no offramp from this ride, and we won’t be able to do it alone. I hope you join me in trying to do our best with whatever comes our way.

A lot of work went into the Fourth Installment of the PhaseShift Newsletter. If any part of it strikes a chord with you, drop a comment! I’d be happy to hear your thoughts, reactions, or critiques. If you like what you see, and see some potential in it, then please feel free to subscribe. You’ll have an option to pay but it won’t be mandatory to read the posts at this time. Additionally—and this is going to sound funny to say—if you feel like sharing to those in your network, that could help connect it to precisely the audience who may need to see it most. Thanks, and I’ll see you next time.

Can't believe I listened to this whole piece. very ye opening, holy cow

This was an outstanding thesis explaining how we traversed the frothy seas of the pre-internet and found our online activity captured by big business. Now we're so entrenched and disillusioned by information warfare that the world seems to be losing hope for whatever could possibly lie ahead. I know I'm not alone in my fears. I'm really glad to have discovered thinking like yours that can seem to light a path towards some kind of relief, even if we don't know what it might look like yet. Kudos